The Rising of Easter week 1916 came to an end on Saturday 29th April when Patrick Pearse led the official surrender of the Irish rebels to Brigadier General Lowe. The leaders of the Dublin garrisons each in turn surrendered as the news was brought to them over the next couple of days. The rank and file Volunteers had another option; to disappear back into their communities and continue to fight for independence. They would have had to have laid low, knowing that as they had been drilling (many in uniform) in public since 1914, they could be easily recognized by the authorities as an Irish Volunteer or Irish Citizen Army member. For some going ‘on the run’ was the only option. Liam Mellows, the leader of the Rising in Galway, was one such man.

This piece of black gossamer cloth fashioned into a veil, was worn by him as he escaped to England after some months on the run in Ireland. He was accompanied by Pauline Barry, and both travelled disguised as nuns. It was donated to the National Museum of Ireland in 1941 by Sr Lelia MacKenna.

Though the 1916 Rising is remembered mostly as a Dublin event, it was intended by its planners to be countrywide. Branches of the Irish Volunteers and Cumann na mBan in towns and cities such as Cork, Enniscorthy, Limerick and Galway planned the insurrection with the Dublin leaders and awaited the arrival of weapons and ammunition into Ireland and for the final commanding orders to proceed with their plans. Those 20,000 weapons, organized by Roger Casement to come from Germany on the SS Aud, failed to reach Ireland when the ship was intercepted by the British Navy on 20th April. This was to be a major factor in the failure of the Rising.

The order to start the rebellion was quickly followed by Eoin MacNeill’s countermanding order on Saturday 22nd April. This confusion led to many Volunteers not turning out, or being unsure of what action to take. Outside Dublin, by the time couriers reached them with the news that the Rising had started in the capital the regional police and army had already been alerted, making action impossible. Because of this, armed insurrection took place in only a handful of areas outside Dublin; to the north Louth, Meath and Ashbourne saw fighting, and the Volunteers proceeded with the Rising in Enniscorthy and Galway.

In Galway about 2,000 men had joined the ranks of the Irish Volunteers which had been organized by Liam Mellows since March 1915. It drew much of its membership from the strong IRB movement in the area, led by Tom Kenny, which had its root in the region’s large agrarian community. Mellows had been arrested in Tullamore and deported to Reading Jail in March 1916, and Laurence Lardner was commanding the battalion in his absence. However, he escaped, arriving back in Ireland disguised as a priest on Easter Monday.

Early that morning the Galway Volunteers received news that the rising had been called off, only to be followed later that day with a message from Pearse that the rising had started in Dublin and the Volunteers were to proceed with their plans – to occupy police barracks and send men to Tralee to collect arms; a redundant task considering the arms had not landed. Many of the Volunteers that had gathered now dispersed, lessening their numbers, though others continued, attacking police barracks in Clarenbridge, Oranmore and Gort on Tuesday. On Wednesday a group of Volunteers came face to face with the Royal Irish Constabulary at Carnmore Crossroads. Shots were exchanged, and Patrick Whelan, aged 34, an RIC Constable with 8 and a half years of service, was killed in the confrontation.

The now 500 strong group of Volunteers under Mellows’ command gathered in Athenry, armed with a small number of rifles with about 30 rounds of ammunition each, old shotguns and other weapons. This lack of arms and ammunition ensured no further attacks could happen and they began retreating further to defensive positions. While camped at the abandoned big house at Lime Park rumours of a large oncoming military forces began to circulate, and the Volunteers finally disbanded at Moyode on Saturday.

Most of the rank and file rebels were arrested and deported to English jails and Frongoch the following week. Laurence Lardner went into hiding in Belfast, Tom Kenny travelled to Boston and Mellows, along with two of his officers – Alfie Monaghan and Frank Hynes – decided to try to return to Dublin via Limerick. They were on the run for the next five months, escaping over the mountains of Derrybrian and into the mountains of Co. Clare.

Sean McNamara of Crusheen, Co. Clare described these months for Mellows, Monaghan and Hynes in his witness statement. Michael Maloney discovered the three men on his land in the Knockjames area and, being himself a member of the IRB and Irish Volunteers, brought them to a hut on the land and supplied them with food. He told McNamara as his commanding officer, who began to collect funds to support them, including over £100 from the Daly Family in Limerick. The men spent five months in the Knockjames mountains hut, and McNamara describes this time almost fondly – ‘Liam had his violin , there were visitors, music and songs, often a wrestling bout and always the Rosary in Irish led by Liam’. In October Volunteer Michael Fogarty brought the order from GHQ Dublin that Mellows should go to America. McNamara was to accompany Mellows to the house of Fr Michael Crowe, the parish priest of Kinvara, who had procured two nun’s habits which were to be used by Mellows and Miss Pauline Barry of Gort as a disguise. McNamara leaves them with Fr Crowe, who later reported that the two ‘nuns’ had attended mass at 6.30am the next morning, describing Mellows as ‘the most perfect nun in appearance that I ever saw’.

They then travelled as a group – Fr Crowe, Bluebell Powell dressed as a novice and the two nuns – by car to Cork, calling at hotels and convents along the way, Mellows’ disguise holding throughout the day.

Mellows travelled in this disguise from Cork to Liverpool, and made his way to the house of Republican Peter Murphy. Murphy worked for the Liverpool and Mersey District Shipping Federation, an Employers Association, and, along with his assistant, he began making arrangements to get Mellows onto a ship to New York. Mellows stayed in this house in Liverpool for two weeks. Nellie Gifford-Donnelly, one of the founding members of the Irish Citizen Army and a combatant in the College of Surgeons during the Rising, was also on the run there, waiting to get to America on a false passport.

Murphy arranged for Mellows to sail as a coal trimmer under the name of John Atheridge on a tramp steamer. Nellie helped disguise Liam by dying his hair, and he joined a ship which sailed first to Barbados and then New York, arriving after 6 weeks at sea. During that journey Mellows had risen to the position of Leading Stoker before the ship reached New York in about December 1916.

Mellows began work with John Devoy on the Gaelic American newspaper, but was soon arrested by the US authorities and imprisoned in the Manhattan Detention Complex in New York, charged with aiding the German enemy. He was released in 1918, and continued to tour the US, speaking for the Republican cause, and helped organize Eamon de Valera’s fundraising trip to America in 1919-20. On his return to Ireland he continued activity through the War of Independence and opposed the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921. He was one of the 77 men officially executed by the Irish Free State Forces, being shot on the morning of 8 December 1922, aged 30.

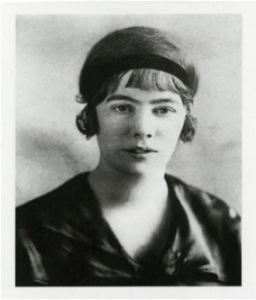

It is sometimes difficult to square this strange relic with Liam Mellows. There is no denying that there is an element of humour to this story, which is not normally associated with the Liam Mellows we are presented with. Images of him show a young man with a serious demeanor. It is evident in his face that he is an intelligent and understated man. We know that he was able, determined, dedicated to his beliefs, and clearly very hard working. From a young age he was held in very high regard by Thomas Clarke and James Connolly, and was entrusted with the task of mobilizing the west of Ireland. He earned the trust and respect of the men he led. He would of course have been aware in his months in hiding and during his escape that his capture could very likely lead to his death. But I can’t help but wonder if, when handed this black veil to wear, he raised a smile, or perhaps an eyebrow.

© Brenda Malone. This work is original to the author and requires citation when used to ensure readers can trace the source of the information and to avoid plagiarism.

https://libguides.ucd.ie/academicintegrity/referencingandcitation

Sources and general reading used in the creation of these articles are listed on the Further Reading page.