1941 saw Ireland commemorate the 25th Anniversary of the 1916 Rising, an event which saw the largest national marking of the event up to that point. The National Museum of Ireland in Kildare Street had already held two exhibitions on the Rising; Nellie Gifford-Donnelly, a founding member of the Irish Citizen Army who had also fought at St Stephen’s Green during Easter Week, curated the first 1916 Exhibition in 1932, timed to coincide with the Eucharistic Congress being held in Ireland that year. The display was installed again in 1935 with the title ‘Relics of the Fight for Freedom’. From that time, there has always been a display on the Rising, and renewed for every significant anniversary.

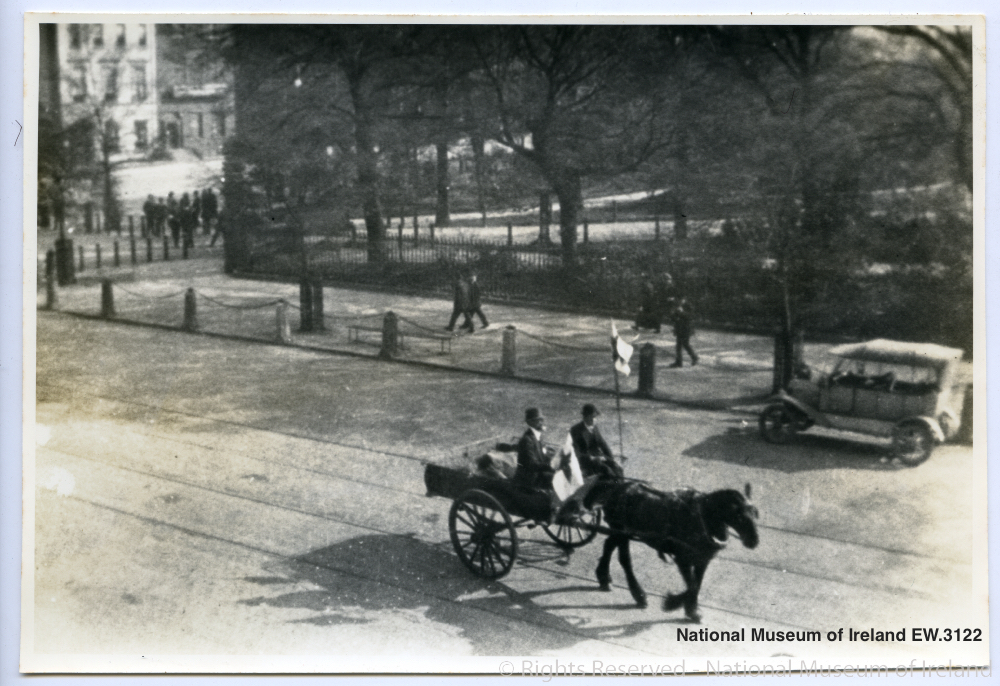

This series of photographs were taken during the installation of the 1941 exhibition as part of the preparations, with the images of the opening used to publicise the display in newspapers, and were found amongst the Easter Week and Historical Collections. They show the museum staff at work in the days before the anniversary, and the public visiting the displays.

The 1941 exhibition, which was simply named ‘The Exhibition to Commemorate the 25th Anniversary of the Rising’, was curated by Dr Gerard Hayes-McCoy, a renowned military historian, who had taken a curatorial post at the National Museum in 1939.

When Hayes McCoy took up this position he immediately began collecting objects which represented the rebellions and wars previous to 1916, which he felt was not only important to include in our national collections but also necessary in order to outline Ireland’s fight for independence during the centuries before 1916 to explain its roots.

Items representing the Fenian Movement, Robert Emmet, Joseph Holt and Charles Stewart Parnell were collected and exhibited for the first time. The exhibition location was moved from a side room into the central gallery space of the Kildare Street museum, normally only used for the archaeological collections such as the Ardagh Chalice and the Tara brooch.

Before it opened on Easter Saturday 12th April, newspapers across the country published the National Museum’s press release on the exhibition’s content, written by Hayes McCoy.

Relics of 1916 Anniversary Exhibition

The National Museum, Kildare Street, Dublin, will be the scene of a striking exhibition of relics connected with the events and personalities of the Rising of Easter Week, 1916, and the succeeding epochs on the occasion of the 25th Anniversary. The special collection is already well known and since its foundation in 1935 has materially increased. The opportunity has been taken to display the Collection on a more extended basis utilising the large courts adjoining the museum entrance at Kildare Street now being prepared. No pains are being spared to make the Commemorative Exhibition worthy of the occasion and it is expected that a large public will find it worthwhile visiting when opened on Easter Saturday next, 12th April. The Museum Rotunda will be occupied with a notable group of exhibits illustrating by personal or other relics the political history of the country from some time after the battle of the Boyne when national thought took an entirely new trend till the beginning of the present century. It is intended to illustrate the historic background of the various movements out of which the Republican Movement arose and into which various lines of political thought were canalised. The exhibition proper will show the uniforms of the various military groups participating in the Rising and the aftermath, arms and other details of equipment, relics of the leaders and will include such varied items as a collection of watercolours of Countess Markievicz, the Childers Memorial Collection and numerous items illustrating the growth of the organisation. A small exhibit illustrative of the Gaelic League will also be included. It is hoped that the exhibition will lead to the inclusion in the Collection of numerous relics still in private hands. There will be no charge for admission.

The opening was attended by Thomas Derrig as the Minister for Education, Frank Fahy, Speaker of the Dail, Oscar Traynor as Minister of Defence, and Senator Margaret Pearse, also the sister of Patrick and William Pearse, who were photographed touring the exhibition.

And inspecting the 1920 experimental mortar, or ‘big gun’, made in the basement of 198 Parnell Street, Dublin, underneath the bicycle shop and covert munitions factory of Archie Heron and Joseph Lawless, which exploded and killed Matt Furlong during testing.

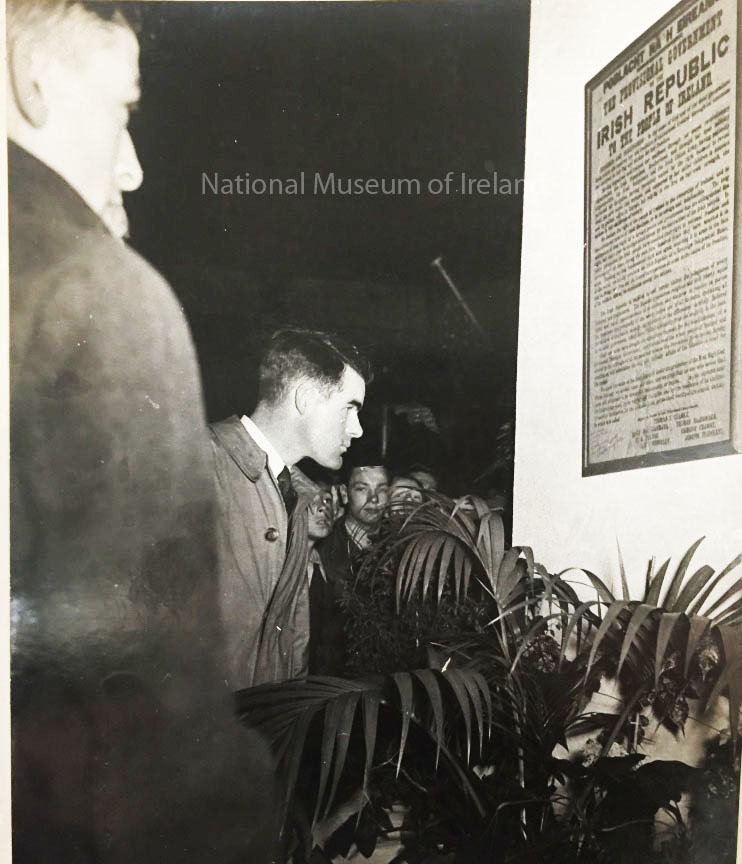

The exhibition proved very popular with the public and the galleries were crowded with people viewing the relics of the period, such as this gentleman viewing (a little too closely for my comfort) an original 1916 Proclamation signed by Christopher Brady (printer), Michael Molloy and Liam O’Brien (compositors).

It was visited by school groups, as seen in this wonderful image of these girls in beautiful traditional Irish costume being shown a display of rifles used during the revolutionary period by a gallery attendant.

And this group posing for a photograph underneath the statue of Patrick Pearse and the Proclamation.

The Irish Army attended for special tours and talks.

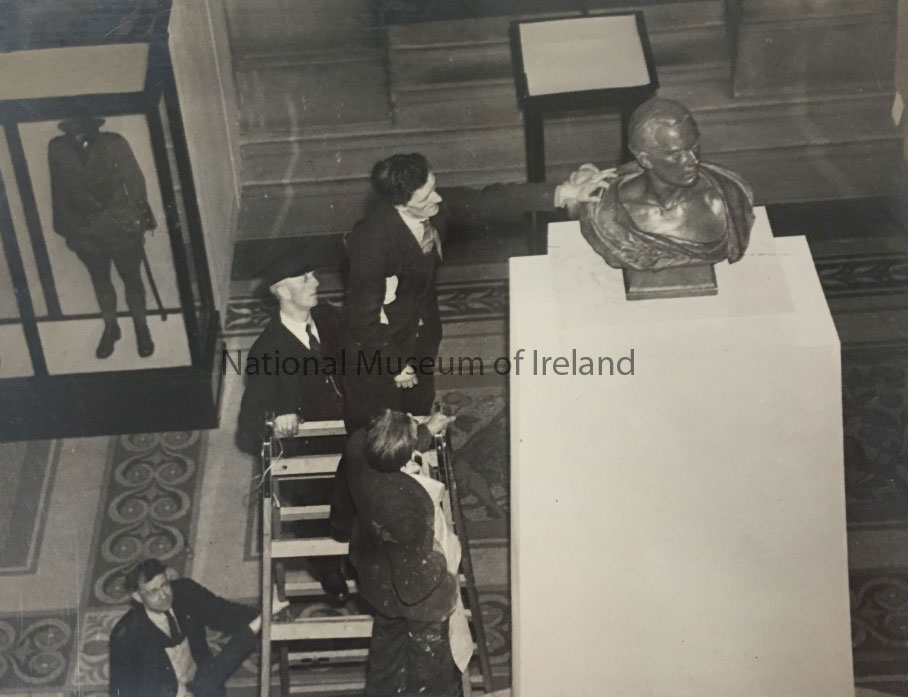

Some of my favourite photographs are those showing the collections and technical staff working to install the exhibition. They show artefacts being mounted into wall cabinets, the uniforms of both Michael Collins and Liam Lynch being mounted onto mannequins, mounts being built, statues being restored, and large objects set on top of plinths.

This female collections staff member holds a document up for the camera, while beside her we see what is probably a tricolour flag and the umbrella given to Patrick Pearse by his students at St Enda’s School as a gift in 1910. I just recently photographed and re-housed this umbrella, and seeing photographs like this, with this same artefact 77 years ago, really brings home to me how we are all only temporary custodians of our national collections, which will continue to exist, be cared for, interpreted and displayed beyond our own lives in the museum.

Sadly I have no names to go with these faces. If you or anyone you know has any information on NMI staff in 1941 I would love to hear from you.

© Brenda Malone. This work is original to the author and requires citation when used to ensure readers can trace the source of the information and to avoid plagiarism.

https://libguides.ucd.ie/academicintegrity/referencingandcitation

Sources and general reading used in the creation of these articles are listed on the Further Reading page.