I came across a wonderful original photograph album in the stores last week. It’s a little unusual, as many of the albums we have in the collection are of souvenir postcard photographs showing the destruction of the city centre after the Rising, which were on sale quite soon after the event. The album is described simply as photographs taken after the Sinn Fein Rebellion May 1916, with handwritten notes describing the location of each photograph, and was acquired by the museum from a Mr Smith in 1975.

As I went through it a particular image caught my eye. It was a little different to the others, which were shots focusing on the damaged buildings and streets. This photograph had no apparent focus, until I looked very closely. The text underneath reads ‘The first British airship to visit Dublin coming up Sackville Street’. And there, only vaguely visible over the street, is an airship! Also noticeable in the photograph are groups of people looking upwards in its direction; a group of people have gathered around the statue of Sir John Grey in the centre of the street, and to the right of the image the drivers of a horse drawn cart appear to be turning around to get a view of it.

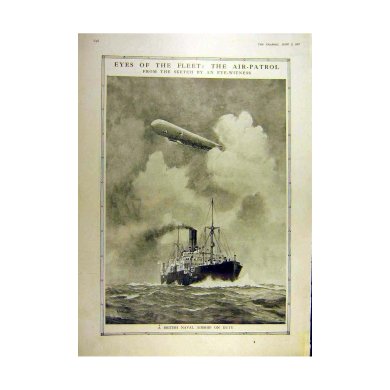

This unusual event was reported in The Irish Times on 27 May. ‘A British airship, flying the naval ensign and bearing the Allied distinguishing mark – coloured circles – on its rudders, appeared over Dublin yesterday (Friday 26 May), and attracted very keen attention. It was first noticed east of the Custom House, and, after flying over the neighbourhood of Amiens Street Station, passed over the ruins of the Imperial Hotel, crossed Sackville Street, then turned south nearly as far as the offices of the Port and Docks Board. It then proceeded eastwards over the Liffey, and performed some evolutions over the buildings on the South Wall. As it came low an excellent view of its design was obtained by the hundreds of persons observing its movement. Three figures could be seen in the airship. The navigating officers acknowledged the cheers of the crowd by waving their hands’.

Another airship was sighted a month later on Thursday 20 July, and the Irish Times described it as an airship ‘of a type not previously seen by the citizens’, which manoeuvred slowly over the city for about half an hour.

This begs the question as to why this airship flew over Dublin on these days.

A second photograph shows it passing over D’Olier Street, which is clear enough to identify what type of airship it was.

The shape of the balloon envelope and the car underneath matches the SS Class blimp (Sea Scout or Submarine Scout) which the Royal Naval Air Service put into production in February 1915 after the Imperial German Admiralty declared that all enemy merchant vessels found in the waters around Great Britain and Ireland would be destroyed. These airships were equipped with bombs and a Lewis machine gun, as well as a camera, and would act as escorts for ships to protect them from the threat of the German U-boat.

As the SS Class blimp carried a camera, I suspect the purpose of this ship’s flight over Dublin was to take aerial photographs of the city centre. Aerial reconnaissance was well established by 1916, and there had been major developments in the quality of cameras. It is estimated that over a million photographs were taken by British forces during the course of World War I. If the Dublin airship did take aerial shots of the post-Rising city I have not yet found them in a public collection, but I will keep looking.

So was this the first visit of an airship to Dublin? The first airship stations in Ireland, such as Malahide and Johnstown Castle in Wexford, weren’t built until 1918, so this airship must have travelled from a station somewhere around the west coast of Britain, the closest being Anglesey and Pembroke, or was possibly on anti-submarine patrol in the Irish Sea. Ces Mowthorpe, in his book Battlebags, records that the SS-17 broke free of its moorings in Luce Bay in Scotland, probably sometime in 1915, and drifted across the Irish Sea, complete with crew, until they were able to land in Ireland. However, that ship most likely landed in the northern Irish counties, so this rare photograph in the Smith album may well be an image of the first airship in Dublin.

© Brenda Malone. This work is original to the author and requires citation when used to ensure readers can trace the source of the information and to avoid plagiarism.

https://libguides.ucd.ie/academicintegrity/referencingandcitation

Sources and general reading used in the creation of these articles are listed on the Further Reading page.