Probably the most famous flag of the 1916 Rising is the Irish Republic flag, with its white and orange lettering on a green field background. It was flown from the roof of the GPO on the Princes Street corner, while the tricolour flew from the Henry Street side. The flag survived the destruction of O’Connell Street, and was taken as a war souvenir by the Royal Irish Regiment. It ended up in the collection of King George of England, and was stored in the Imperial War Museum until 1966 when it was presented from the British to the Irish governments for the 50th Anniversary of the Rising. It is now in the care of the National Museum of Ireland.

Another 1916 Rising flag that was presented to the National Museum was less fortunate in its survival. These fragments of the tricolour flag that flew from the tower of Jacob’s Biscuit Factory also made the journey from England to Ireland in 1966. They are glued onto a piece of paper from a photograph album, with the words ‘Fragments of the Sinn Fein Flag which flew over Jacob’s Biscuit Factory, Dublin, Easter 1916’.

On the Monday morning of Easter week the rebels took a number of buildings across the city. They hoisted flags from the highest points of these buildings as a symbol of the new Republic which had just been declared. The GPO’s Irish Republic and the Irish Citizen Army’s Starry Plough flag, flown from the Imperial Hotel, were unique. The other garrisons flew either the Irish tricolour of green white and gold, or the gold harp on a green field background. Many were made beforehand in preparation for the Rising and stored at Liberty Hall, but the Jacob’s tricolour was made at the garrison post during the week.

The garrison at Jacob’s Biscuit Factory saw a limited amount of action that week (the story of Jacob’s garrison that week can be read here). The men were mostly involved in sniping at British soldiers coming towards the city from Portobello Barracks and providing other garrisons with both supplies and men.

Thomas Meldon was part of the garrison, and says in his BMH witness statement that they had forgotten to bring their flag with them as they marched out of Liberty Hall on Monday morning. On Thursday they received a message that the GPO was burning, and that the flag had been shot or burnt down. They decided to make a flag, and the search for the materials began.

‘After some time a quantity of bunting was found, some green and some white, but, curious to relate, no orange – stalemate, but not defeat.

A further search brought to hand a bundle of yellow glass cloths, and the work of putting together the flag was commenced. Three men were entrusted with this task – George Ward, who has answered the last call-in; Derry Connell, who is still with us, and myself. On the completion it was discovered that the rope on the flagpole had been removed, so that the flag had to be nailed to the pole, needless to say, at the risk of life. Nevertheless, it was accomplished, and according to a little book by James Stephens, the author, on that memorable week, the flag was still flying long after the general surrender.’

In fact, James Stephens, in his book The Insurrection in Dublin, described how he could see the flag flying from Jacob’s from his kitchen window on Sunday, and saw it being hauled down at about 5pm that evening.

We also have some insight as to what was happening in the factory at that moment. Patrick Cushen, an employee of Jacob’s, came to the building on Sunday afternoon after the surrender of the Volunteers to protect the factory from looters. He left an account of the scene he found, including meeting John MacBride and the hauling down of the tricolour flag –

‘Having heard of the rebels’ surrender of the factory, I ran down and saw about 90 of them getting out the windows and a lot of the rabble getting up the rope that was hanging from the office window, and tumbling the sacks of flour out. I ran round to the Caretaker’s door in Peter Street and got in to the Bakehouse. I was surprised to see between 90 and 100 of the rebels standing and sitting about.

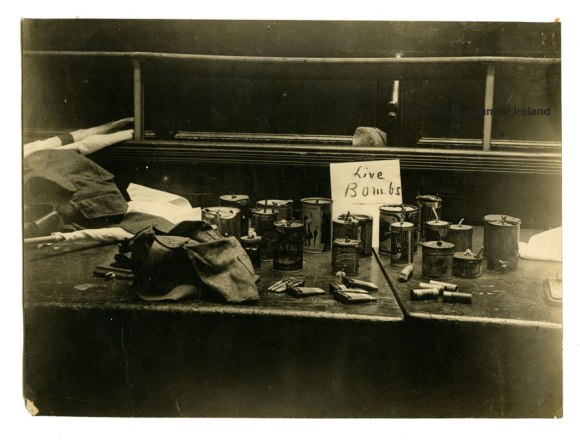

Then one of the officers of the rebels came in to the office and asked was there anyone to take charge of the place, and they told him that I would. He said there were a lot of bombs stored away that would blow up the whole place, and as they had done no damage they did not want the blame to be left on them if any careless person handled them. He brought me round and pointed them out to me, and we came back again and he showed me where there were some hand grenades stored in the little ovens in the King’s Own Room; he left me on guard of them and told me on peril of my life not to let anyone lay a hand on them until the military came in who knew what they were.

He went away after making himself known to me, and to my surprise I found myself introduced to Major MacBride for the first and last time, as we all know he paid for his mad acts with his life.

Well, he was not well gone when a volley of shots rang out all round about where I was standing, and the sprinkler main over my head was pierced through with a bullet, and the hat was knocked off my head by a bomb fired through the open window. Luckily for me it passed out through a window and exploded over the refrigerator outside. Well, I thought my last hour had come. Just then the soldiers came in and shouted ‘hands up’, and up they went in haste, then they came over and searched me, asked me who I was and what had me there. I told them that I was an employee of the firm and that I came in to stop the looting. They said, ‘if you are a member of the Works, you know where that d… rebel flag is hanging out, and get on to it at the point of the bayonet’.

I said ‘you are not one bit more eager to get it down than I am myself, but before I go I want to show you those weapons of danger – the bombs’. Then we started on our way to the flagstaff, and went to three or four doors but could not get in the way they were barricaded. At last we got in through the Cake Room and away to the tower: I would not let him get out for fear of the snipers, but I got the rope and lowered the flag and no sooner than it began to come down than 5 or 6 shots rang out – I do not think that man could have been prouder if he was after taking the Empire of Germany.

On our way back he told me that I was a lucky man that I had nothing in my hands when he came in or he would have shot me where I was standing.’

The card on which the Jacob’s flag fragments are attached takes up the story from where Patrick Cushen left it. On the back is written that it was a gift from a Mr Fowler who was present in the Hotel when the flag was brought in by a Canadian soldier, and relates the following story –

‘A certain time was given for the troops of the IRA to leave Jacob’s and then this Canadian solder entered the building with another soldier. They met a man in uniform and promptly shot him, then a man in civilian attire who they directed to show the way to the flag. On arrival the civilian was told to ‘hop it’, which he promptly did. The flag was hauled down and taken to the Hotel by the Canadian who cut it up into fragments and distributed them to those present’.

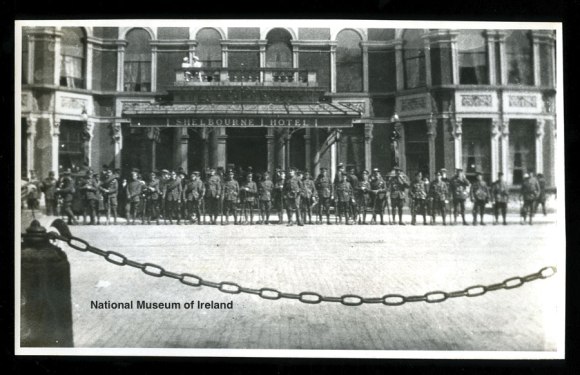

Though there is no further information given with the object to help us identify either the Canadian soldier or the hotel, we can conclude that the hotel mentioned is the Shelbourne Hotel on St Stephen’s Green. The Shelbourne had been taken over by British troops and used as a base from where they fought against the Irish Citizen Army, led by Michael Mallin and Countess Constance Markievicz, at the Green and the Royal College of Surgeons, and is around the corner from Jacob’s Factory.

By Friday of Easter week, between soldiers in Irish Regiments in the British Army and the arrival of 10,000 British troops from England (diverted from the fighting in France), there were about 16,000 British Army soldiers in Dublin.

Our Canadian soldier however, was not one of those sent from England on the Wednesday and Thursday, nor was he stationed in Ireland. He was most likely in Dublin on leave from the war at the Front, as were many other soldiers from British Commonwealth nations such as Australia and New Zealand. When the Rising started, these soldiers reported for duty to their nearest barracks or to Trinity College which was also operating as an Officers Training Corp (and held a stock of arms), and so formed part of the body of soldiers involved in the suppression of the Rising.

However, the tale he told to those in the hotel that he had entered Jacob’s Factory and shot a man in uniform is not factual. Not only did Patrick Cushen not mention any incident of a shooting, but there are no records of any combatant death occurring around Jacob’s other than Irish Volunteer John O’Grady, who was mortally wounded around the Mount Street area while trying to reach the Boland’s Mills garrison. It seems the Canadian soldier’s statement was an ill-advised boast to his audience.

The Jacob’s Factory flag fragments will be on display in the National Museum of Ireland’s new exhibition Proclaiming a Republic: The 1916 Rising in the Riding School at Collins Barracks in March 2016, along with the rest of the museum’s collection of 1916 garrison flags, including the Irish Republic and Starry Plough. Though it is not be the only garrison flag in the museum’s collection, it is certainly the smallest.

© Brenda Malone. This work is original to the author and requires citation when used to ensure readers can trace the source of the information and to avoid plagiarism.

https://libguides.ucd.ie/academicintegrity/referencingandcitation

Sources and general reading used in the creation of these articles are listed on the Further Reading page.

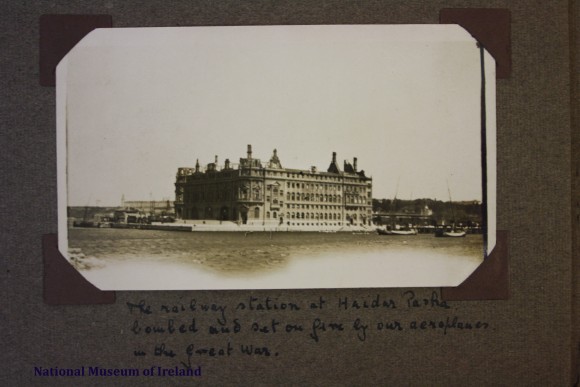

Lt Andrew Horne’s Gallipoli photograph album will be on display and fully viewable in digital format in the World War I Centenary exhibition in the National Museum of Ireland, Collin Barracks, opening end of November.

Lt Andrew Horne’s Gallipoli photograph album will be on display and fully viewable in digital format in the World War I Centenary exhibition in the National Museum of Ireland, Collin Barracks, opening end of November.

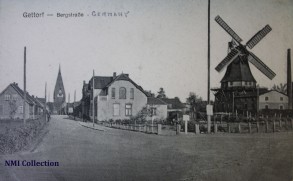

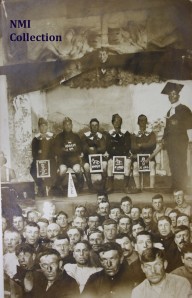

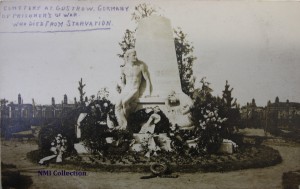

eph returned home in December 1918, one month after the armistice, on the Norwegian liner the Frederik VIII, which had been chartered by the British government to transport their men back from Germany. Though the McEnroes’ story reflects the experience of many Irish families during the Great War, they are unusual in one way – they both survived. At a time when Irish households, and sometimes whole streets, were receiving news of the death of their loved one, Frances McEnroe was lucky enough to have both her sons live through serious injury and imprisonment and return home.

eph returned home in December 1918, one month after the armistice, on the Norwegian liner the Frederik VIII, which had been chartered by the British government to transport their men back from Germany. Though the McEnroes’ story reflects the experience of many Irish families during the Great War, they are unusual in one way – they both survived. At a time when Irish households, and sometimes whole streets, were receiving news of the death of their loved one, Frances McEnroe was lucky enough to have both her sons live through serious injury and imprisonment and return home.