The National Museum of Ireland has a gathering of wildly diverse objects within its historical and decorative collections – The Presidential Collection. These items are a selection of the gifts presented to the Irish President from both visiting foreign dignitaries and national organisations since the foundation of the State, the earliest items relating to Douglas Hyde.

Ethics in Public Office regulations state that gifts over a certain value (currently set at €500) received by a servant of the Irish State remain the property of the Irish State.

While most gifts remain in Áras an Uachtaráin as state property, a selection was transferred to the museum in the early 1990s, including a recent gift – a rug given to President Patrick Hillery (1976-1990) by Saddam Hussein.

However, the gift that took my interest is the ceremonial horse saddle presented by Colonel Muammar Gaddafi to President Eamon de Valera in 1972, at the height of The Troubles and arms smuggling from Libya into Northern Ireland.

The gift is comprised of a saddle, a bridle, riding whip and saddle cloth, all elaborately decorated in the traditional North African style. Sporting a leather seat and harness laced with silver embroidery designs, coloured stitching and silver stirrups attached from red leather straps, the saddle rests on a wool blanket, providing some comfort for the horse, which is also decorated in traditional style with a coloured leather patch and multi-coloured wool pom-poms.

The saddle cloth is bordered with gold embroidery and fringe, with blue and silver designs on a field of rich red. The set was gifted with a matching bridle and riding whip. Such saddles are handmade by artisans who pass the skill from generation to generation, and were widely used at occasions such as weddings and horse racing competitions as well as official state ceremonies.

While the gifting of a traditional emblem of the visiting dignitary’s country to the host country is a very common custom worldwide, it is the circumstances and timing of this gift from Libya to Ireland that makes the saddle intriguing, as is revealed in the official state papers from 1972 held by the National Archives.

By 1972 Éamon de Valera had already led a long life in Irish politics. He had been a leader in the recruitment of men to the Irish Volunteers in the Irishtown and Donnybrook area from 1914, the commander of the Boland’s Mills Garrison during the 1916 Rising, narrowly escaping execution by the British authorities, a leading figure in the War of Independence, President of Dáil Éireann and the leader of the anti-Treaty forces during the Irish Civil War. He founded a new republican party – Fianna Fáil – in 1926), and was the President of the Executive Council and Taoiseach of Ireland four times from 1932 to 1959. He was later elected as President of Ireland – the non-political figurehead – from 1959 to 1973, retiring at age 90.

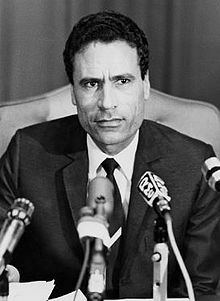

Muammar Mohammed Abu Minyar Gaddafi, known simply as Colonel Gaddafi, was born in 1942 to a Bedouin family near Sirte, west of Tripoli on the Mediteranean coast. He was a political activist from an early age, and having decided a career in the military would best serve his political ambitions, he attended the Royal Military Academy in Benghazi and later in England.

In 1964 he had established a revoluntionary cell within the Libyan Army – the Free Officers’ Movement – which Gaddafi led to overthrow the monarchical government in a coup in 1969 to establish the Libyan Arab Republic, based on the principles of ‘freedom, socialism and unity’ and led, essentially, by Gaddafi himself. He and his Revolutionary Command Council began a series of reforms to bring Libya in line with the revolution; such reforms included stimulating economic growth such as the agricultural sector production, free health care and a reassertion of women’s equality in Libyan society, though they also included retaining a ban on political parties, banning trade unions and workers’ strikes and suppressing the press. The intellectual classes were imprisoned, and many fled Libya’s new regime, some settling in Ireland as refugees.

Libya’s main export was oil. Gaddafi claimed the trade agreements regarding its sale were unfavourable to Libya and began to control its production, leading to a rise in oil prices worldwide, leading to an inevitable increase in tensions between Libya and the Western nations over the next decades, despite Libya’s efforts to build diplomatic relations.

In March 1972 Galal Daghely, the Libyan ambassador to West Germany, was officially in Ireland to meet with a foreign trade committee, and requested to meet President de Valera. This request was turned down, as it was felt that the purpose of such a meeting was to start the process of establishing an official diplomatic presence in the Republic of Ireland. However, on St Patrick’s Day, Daghely contacted Áras an Uachtaráin saying he had a gift from Colonel Gaddafi to President de Valera, and there would be great disappointment if it were not accepted. The Áras agreed to a short meeting to receive the gift, on the condition that the meeting not be publicised and the visit not be seen as part of an official programme.

De Valera wrote to Colonel Gaddafi shortly after the meeting saying ‘Recently I had the pleasure of receiving his Excellency the Libyan Ambassador in Bonn, Mr Galal Daghely, who had expressed a wish to call on me during his visit to Dublin. On that occasion, he delivered to me the saddle, bridle and riding whip which your Excellency so kindly sent to me. For this gift, which richly reflects Arab skill and handicraft, I wish to convey to your Excellency my sincere thanks. In expressing my appreciation of your kindness, may I add my good wishes for your personal well-being.’

Áras an Uachtaráin was likely to have been very relieved that the meeting to receive a simple gift had not been known publically when, the following year, the Irish Naval Service intercepted the cargo ship Claudia off Helvick Head in Co. Waterford and found it to be transporting a 5 ton arsenal of AK-47s and Semtex explosive to Northern Ireland for use by the Provisional I.R.A. This shipment had been arranged by I.R.A. chief Joe Cahill with the Gaddafi regime in Tripoli in late 1972. Libya became a major supplier of arms into Northern Ireland over the next decades, providing rifles, machine guns, handguns, explosives and even RPG-7 rocket launchers into the late 1980s.

Gaddafi never made any secret of his country’s role in supplying the arms to the I.R.A., seeing it as a fight against the colonialism he himself hated (Libya having been occupied by Italy from 1911 to 1947, when Italy lost its colonial territories under the Treaty of Peace with Italy after World War II).

After a bombing campaign in Britain in 1976, Gaddafi publically stated that the bombs used were Libyan bombs in retaliation for past deeds, and refused to state that he would stop sending arms to Northern Ireland.

For some years there were few political consequences for Gaddafi’ regime; the Irish Government decided in 1973 that taking official action over the arms risked provoking the regime into increasing their activities and providing more arms to the north.

There were also trade concerns regarding oil supply to the West. Great Britain did not break off relations with Libya until the 1984 shooting of policewoman Yvonne Fletcher, who was on duty when she was killed by a bullet fired from the Libyan Embassy in London during an anti-Gaddafi protest. Soon afterwards the US retaliated against the bombing of a Berlin disco in which an American soldier was killed with an air raid on Tripoli, killing over a hundred people. In 1988 the Lockerbie, Scotland, bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 and the death of 270 people caused the UN to impose sanctions on the Gaddafi Regime until 1999, when the Lockerbie bombing suspects were returned to Britain for trial. Gaddafi remained in power until the revolution of 2011, with his forces turning on the citizens who stood against them, eventually leading NATO to intervene on the side of the rebels. Gaddafi went into hiding but was killed outside Sirte, his birthplace, ending his 42 year rule.

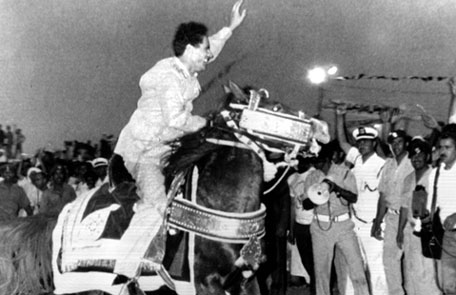

The saddle gifted to de Valera and the Irish State was not unique. A similar saddle had been presented to Malta’s Prime Minister Dom Mintoff in the 1970s before relations with the West soured. Mintoff was later asked by Gaddafi to aid him in a purchase of a nuclear submarine, which he refused. On close inspection of the photograph of Mintoff’s saddle, one can see that the decorative saddle cloth is the same design as the one presented to Ireland.

Gaddafi also presented a saddle to British Prime Minister Tony Blair in March 2007, after their meeting in a Bedouin tent in the desert outside Tripoli. This meeting was part of the re-building of relations, with Libya having disarmed itself of weapons of mass destruction. BP Oil Chairman Peter Sutherland, who was also at the meeting in the desert, announced the signing of a new deal to the value of st£13 billion.

Both the Malta and UK saddles were sold at auction in the last few years.

The Gaddafi saddle in the National Museum of Ireland will remain in our collections as an artefact of a complex and multi-layered history.

© Brenda Malone. This work is original to the author and requires citation when used to ensure readers can trace the source of the information and to avoid plagiarism.

https://libguides.ucd.ie/academicintegrity/referencingandcitation

Sources and general reading used in the creation of these articles are listed on the Further Reading page.