As the fighting of Easter Week raged through parts of the city, other areas, even if they did not experience heavy combat, were also affected. The streets around the Volunteers’ garrison posts were dangerous places to be, particularly for the civilian inhabitants. O’Connell Street saw much looting in the first couple of days of the week as people took the opportunity to get new clothes and luxury items such as sweets, normally out of the reach of the poorer city centre residents. In most of these city centre locations it was the tenement dwellers who were caught in the crossfire between the rebels and the British Forces. Some, such as the men and boys in North King Street, were deliberately shot in the belief they were part of that rebel force. It was clear from early on that whether Dubliners took part in the Rising or not, their lives would be changed by it.

This framed print, depicting a glamorous Edwardian lady wearing an elaborate hat, was hanging in the home of Annie Mac Swiney at No. 5 Belvedere Place, located between Mountjoy Square and the North Circular Road. On Thursday 27th April, a bullet entered the room, barely missing Annie, piercing the picture and lodging in the wall behind it. Both picture and bullet were kept as a memento, and it was donated to the National Museum in 1941, on the occasion of the 25th Anniversary.

Annie lived at 5 Belvedere Place with her sister Mary. The house was owned by Sarah Lowry who ran it as a boarding house, living in 11 rooms with her 5 lodgers. In the 1911 census her tenants included drapers’ assistants William Lane and Kathleen Murphy, Laura McGuire – a stenographer and typist who had been born in India, butcher’s assistant Patrick Sullivan and Christopher O’Conor who listed his occupation as Commissioner of New York – a wide cross-section of Dublin citizens!

The Mac Swiney sisters lived at 5.2, a self-contained, separate unit in the building. The sisters shared one room, in which all their household activities was carried out, from to preparing food to sleeping. In 1901 they had also been living in a single room in a nearby tenement at 20.8 Temple Street, but sharing the building with 23 other people; their situation was certainly improved in Belvedere Place.

Neither Annie nor Mary had ever married, but both women worked as stationers (sellers of books, paper and writing implements), with Annie also listed as being a relief stamper (who produced engraved or embossed designs on writing paper and envelopes). These were respectable trades for the women and would have provided them with enough to support a modest living together.

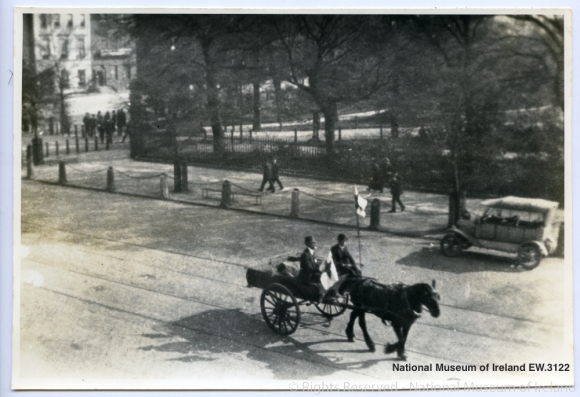

Belvedere Place saw some disturbance due to its position off the North Circular Road, which had military cordons in the area. The street was also home to William O’Brien, living with his family and their boarders at No. 43. O’Brien, a tailor by trade, was also a founding member of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union alongside James Larkin, was highly involved in the 1913 Lockout in Dublin and was a close associate of James Connolly. He was not involved in the 1916 Rising, but his home was used as a safe house for a member of the Connolly family during the week.

O’Brien described what happened on the street, and at his home, in his witness statement to the Bureau of Military History.

‘On Wednesday 26th, a number of soldiers appeared near my residence and were, apparently, taking up positions along the North Circular Road down by Russell Street and Portland Row. At about 11.30 two men, whom I did not know came to my residence with Roderick Connolly, son of James Connolly, aged 15 years, who had been in the G.P.O. from Monday, with a request to my sister that she should look after him. At this time the soldiers appeared to be moving up Belvedere Place towards my residence and my sister and I thought that young Connolly might be safer in some other house than ours, I got my sister to cross the road to a friend’s and ask this lady if she would take Roderick Connolly. The lady agreed to do so, but reluctantly, and was apparently alarmed at the situation. In view of that I decided that it would, perhaps, be safer to keep young Connolly with us, and he remained.

While discussing with my sister the position of Roderick Connolly, I decided that if the British military searched the house, it would be undesirable to give the name of Connolly and so I arranged that he would give the name Carney with the Belfast address of Miss Winifred Carney who was in the G.P.O., so that if there was a check up on the address in Belfast it would look alright. I also coached him to say that he had come to Dublin to look for work and that he was lodging in 43 Belvedere Place and did not know me personally. A number of houses in Belvedere Place were searched, including the houses on both sides of mine, and one or two houses opposite. As soon as the soldiers had got into position, all the residents in Belvedere Place, and I presume in adjacent streets also, were told to keep all the windows completely closed and not to open any front doors. The state of affairs continued on Thursday; many of the soldiers sat on the doorsteps and on one occasion, when I opened the door, I was told immediately to keep it closed’.

It was on this day, Thursday, that the picture hanging on the Mac Swiney sisters’ wall was shot by the stray bullet coming into their home. Although there was no heavy fighting around this street, there was clearly some gunfire here, whether it was a deliberate shot that missed its target, a stray bullet from a neighbouring street, or if it was the nervous discharge of a weapon by an inexperienced young soldier.

The note that came with the picture stated that the bullet narrowly missed Annie, and it must have been a frightening and distressing experience for her. But this bullet pierced picture tells us about more than Annie’s near miss. It shows us how even when the civilians of Dublin stayed in their homes taking cover from the danger on the streets it was still not safe for them – bullets and shrapnel could enter their houses through doors and windows, and many civilians were indeed killed in their own homes, such as 37 year old William Connolly who died of gunshot wound to his chest at his home at 27 Usher’s Quay, and 13 year old Margaret Veale was killed in the bedroom of her home at 103 Haddington Road, off Northumberland Road, the site of the Battle of Mount Street.

We may never know the exact number of deaths that occurred during this week, but it is estimated that about 500 people were killed, the vast majority of these were civilian casualties, numbering just under 300.

There were also about 2500 people injured. From the beginning of the week, the injured and dead were brought to various hospitals around the city. Hundreds streamed into Jervis Street, Mercer’s, Sir Patrick Dun’s, St. Vincent’s, Mater Misericordiae, Holles Street and Dublin Castle hospitals, brought in by the men of the Fire Brigade and the doctors and nurses who ventured onto the dangerous streets to help the wounded, some losing their own lives in their attempts to save others. Some of the stories of these brave men and women were told in the Royal College of Surgeons’ Surgeons and Insurgents – RCSI and the Easter Rising, a fascinating and moving exhibition curated as part of the institution’s 2016/1916 Commemorative Programme.

As is the case with conflict that takes place in an urban area, it was the civilians – the citizens of Dublin – who suffered the greatest number of casualties during Easter Week. The loss of life, serious injury, losing family and loved ones, homes and livelihoods destroyed as their city burned; these events were to change their lives forever. Even a brief look at the Military Archives’ recently released files of the Property Losses (Ireland) Committee shows the impact on the ordinary citizens of Dublin.

This anniversary has been distinctive in its focus in a number of ways – along with the commemoration of the Rising’s leaders and participants, it has now properly recognised the participation of women in the Rising. It has also examined its effect on the lives of the civilians, especially the children, and their violent deaths. In many cases this wish to commemorate has come from the current citizens of Ireland who want to remember all who went through this traumatic event.

Annie Mac Swiney kept this bullet-pieced picture as a reminder of that event, and donated it to the National Museum with the hope that the people of Ireland would remember how she experienced 1916.

It will be on display in the National Museum of Ireland’s new 1916 exhibition – Proclaiming a Republic, at Collins Barracks, from next week.

© Brenda Malone. This work is original to the author and requires citation when used to ensure readers can trace the source of the information and to avoid plagiarism.

https://libguides.ucd.ie/academicintegrity/referencingandcitation

Sources and general reading used in the creation of these articles are listed on the Further Reading page.