During the week of the Easter Rising the site of Jacob’s Biscuit Factory on Bishop Street was occupied by up to 150 Irish Volunteers, Fianna Éireann and Cumann na mBan, led by Thomas MacDonagh, John McBride and Michael O’Hanrahan.

It was surrendered on Sunday 30 April, when one of the Volunteers left this tunic behind. It was donated to the National Museum in 1917.

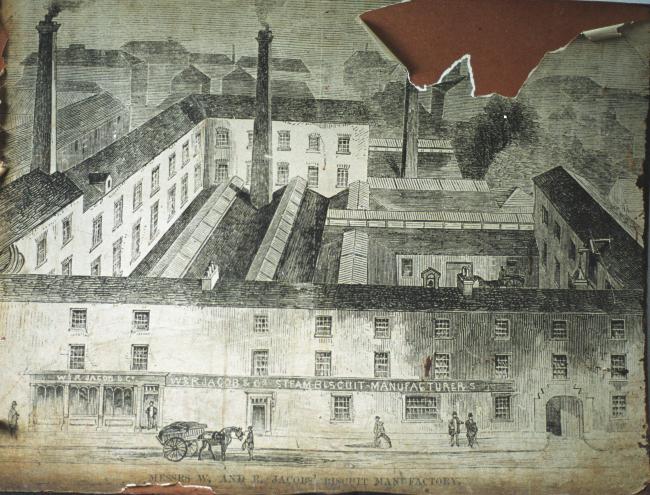

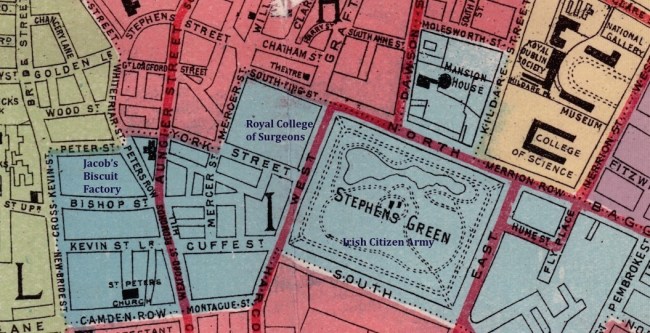

The Jacob’s complex, where the National Archives and DIT Aungier Street now stands, took up a large area between Bishop Street and Peter Street, and was closely surrounded by mostly tenement housing. It was positioned between Portobello Barracks and the city centre and its tall towers made it ideal for sniping – it was therefore a good position to try to cut off military reinforcements travelling to the centre of action.

The main body of Volunteers took the Factory at mid-day on Monday 24th April, and set up outposts in Fumbally Lane, Camden Street, Wexford Street and Aungier Street. The factory was located in the Liberties and Blackpitts area which was quite pro-British, with many families connected to the British Army. The local community, including the ‘separation women’ (the dependents of Irish men in the British Army), was at first hostile to the Volunteers and were verbally abusive to them; one civilian who physically attacked a Volunteer was killed in his defence.

Thomas Slater, in his witness statement to the Bureau of Military History, tells of how they broke through the door with a sledge, politely telling the employee on duty that the best thing he could do was to get his hat and leave, along with any other employees. Being a bank holiday, the factory would have had a minimal level of staff on that day. The men barricaded themselves in, using sacks of flour against windows and doors. As the week progressed the garrison saw little action in the form of assault on the buildings, apart from intermittent rifle fire between the Volunteers and the military, and focused on the sourcing of provisions to feed the men, who were otherwise surviving on biscuits and sweet goods.

In Seosamh de Brun’s beautifully descriptive statement he tells of how the men occupied themselves during rest periods inbetween their duties, when the combatants slept, read books from the Jacob’s library, wrote diaries and even formed study circles. Seamus Pounch relates that the men and women held a céilí during a lull in the fighting.

The Jacob’s men were mainly active in supplying nearby garrisons such as the Irish Citizen Army in the Royal College of Surgeons with provisions, forming parties to gather information on what was happening in the city (the last communication from the GPO was on the Wednesday) and supporting other garrisons by sending men to join the fighting. In particular, a group of 20 men was sent to de Valera’s Boland’s Mills and Westland Row Railway Station, which was under heavy fire from the British Army. When they reached the Mount Street area they were fired on and were forced to retreat, with Volunteer John O’Grady mortally wounded – the only member of the garrison to die that week.

Patrick Pearse officially surrendered to General Lowe on Saturday 29 April, but the news did not reach Jacob’s that day. On the Sunday, Father Aloysius, a Capuchin father, came to the factory with the order. Thomas MacDonagh, refusing to accept the surrender order as binding as Pearse was a prisoner, went with the priest to confer with him in person. Thomas Slater stated that before he left, he told the men ‘to get away if they could, as there was no use of lives being lost’, and many left at this point. On his return, he conferred with the other commanding officers, confirming the surrender order and breaking down with the words ‘Boys, we must surrender, we must leave some to carry on the struggle’.

He called the men to the headquarters on the ground floor to inform them. Michael Walker remembered his words, ‘We are about to surrender but we have established the Irish Republic according to international law by holding out for a week. Though I have assurance from his reverence here that nobody will be shot, I know I will be shot, but you men will be treated as prisoners’ (of war). At this there was uproar, with the men declaring that they did not trust the word of the British, and some urging to continue the fight.

The men had the option of either marching out and surrendering, or escaping. Some took that option; escaping through windows wearing the civilian clothing which had been supplied to them by the Whitefriars Street Priory. Walker was one of these, though he was later found and arrested. Seamus Pounch escaped arrest and had to lay low for some weeks, describing ‘how awkward it was now to have appeared so prominently and so often in uniform in the years leading up to the Rising’.

Vincent Byrne, a 15 year old Volunteer who would later become a member of Michael Collins’ ‘Squad’, remembers being lifted out of a window onto the street to escape, where he was taken into a house by a local woman to brush the telltale flour off his clothing.

Those who officially surrendered were brought to Richmond Barracks before being deported to various prisons and internment camps in Britain. The leaders – Thomas MacDonagh, John McBride, and Michael O’Hanrahan were court martialled and executed the following month.

This Irish Volunteer tunic is of the pattern decided upon by the organisation’s uniform subcommittee in early 1914, and is one of the earliest examples of the type to survive. It was donated to the National Museum in 1917, just one year after the Rising, when its aftermath was still keenly felt by the city, and so it is not only a fine example of contemporary collecting, but is also the earliest object from the 1916 Rising to enter a national cultural institution.

It was found in Jacob’s Factory after Easter Week, and it is likely, given what the witness statements tell us about the surrender, that the Volunteer who wore it made the decision to abandon it before attempting escape. We don’t know who owned this tunic, or whether or not he avoided arrest and internment. I believe that it cannot have been an easy decision for him to make. From a personal perspective, he would have paid for this tunic on a weekly basis over a long period of time, and a number of small, neat repairs to the breast pocket show how valued it was by its owner.

On a practical level, if he had been arrested in uniform he would have had a better chance of being treated as a prisoner of war (though this did not in fact happen to the arrested rebels), but being dressed as a civilian increased his chances of escape. To abandon his uniform and escape may also have been regarded as dishonourable, despite having the full permission of his commanding officers to do so. We can assume from the pattern of the uniform that he was a member of the Irish Volunteers from at least early 1914, and that he was dedicated to the cause of the Irish Republic. Perhaps he went on with the struggle for independence, as MacDonagh hoped when he surrendered the garrison and himself, wishing to ‘leave some to carry on the struggle’.

© Brenda Malone. This work is original to the author and requires citation when used to ensure readers can trace the source of the information and to avoid plagiarism.

https://libguides.ucd.ie/academicintegrity/referencingandcitation

Sources and general reading used in the creation of these articles are listed on the Further Reading page.

11 replies on “Irish Volunteer Tunic, The Surrender at Jacob’s Factory, 1916 Rising”

nice article but might want to re-check the dates mentioned for the Saturday and the Sunday.

thanks for updating the dates.

Really like your blog. Some interesting material.

Thanks Johnny! For some reason the surrender dates always get me, probably because the surrender order notes (in the collection) are dated the 30th and 31st!

Another great blog entry! Thanks.

Some background on one of the rebels, if you’re interested – Volunteer Seosamh de Brun, mentioned above, was one of those who arrived at Jacob’s in his Volunteer uniform, and escaped capture dressed in civilian clothes. Another object he left behind was his diary, which he had kept since the start of 1916. It’s filled not only with details of his personal life and business life, but also with his day-by-day description of the Rising as it happened. It is, I believe, the only diary of the Rising written “under fire” and provides a fascinating insight into the mind of an ordinary Volunteer, not just in the weeks and days prior to the rebellion, but also during the actual rebellion itself. The contents of the diary will be reproduced in a soon-to-be-published account of Volunteer de Brun’s part in the Rising, and his life leading up to it.

He actually joined the Volunteers at their inception, so it would be fascinating to think that the Museum’s tunic was his … .

Thanks Mick – and I’m very interested in reading de Brun’s diary – do you know when it will be published? I’m always interested in the experiences of the Volunteer, especially the reasons why they joined. It’s such a shame there’s no way of telling from the tunic who it belonged to – I’d love to be able to put a person to the object!

Hi Brenda – publication by Mercier is expected in August this year. The book is called “The 1916 Diaries: Of an Irish Rebel and a British Soldier”, by Mick O’Farrell (that’s me) and will include a transcription of not only de Brun’s diary, but also the unpublished diary of a British soldier who fought in the Sackville Street area, and also made his notes “under fire”. It also has several never-before-published photos of the Rising, including a pic of James Connolly lying on his stretcher surrounded by soldiers beside the Parnell Monument. It’ll be my fourth book on 1916, so I’m afraid the subject is something of an obsession!

Looking forward to more 1916 articles from you – thanks for going to the trouble!

Excellent! I look forward to reading it, and especially interested in seeing the photo of Connolly on the stretcher

Hi Brenda – in case you’re still interested, the book came out last month – “The 1916 Diaries of an Irish Rebel and a British Soldier”, by Mick O’Farrell. I could ask the publishers, Mercier, to send you a copy, if we can say it’s for historical research! Cheers

Mick – that would be fantastic! Thanks so much – and congrats again!

very interested to read account of Jacob’s, My grandfather was at Jacob’s but got away. Have often wondered how

this came about. Now I know. He did continue his activities. Many thanks.

great piece .my uncles michael and john walker were there……michael mentioned above…….very proud of all who took part …… thanks for post.richard walker