The kind of objects relating to the 1916 Rising which have become part of the National Museum of Ireland’s collection over the last century are varied, and by their very nature includes the most ordinary of objects made extraordinary by the events of the time.

This half brick formed part of the wall at Portobello Barracks, now Cathal Brugha Barracks, until April 1916. Embedded in it is a bullet fired by the firing squad which executed Francis Sheehy Skeffington on the order of British Army officer Captain John Bowen-Colthurst. It was given to Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, Francis’ widow, in 1935, and she donated it to the museum in 1937.

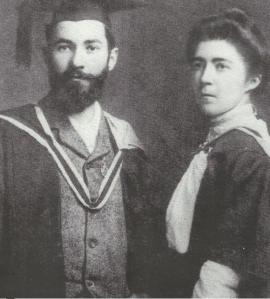

Francis Skeffington met Hanna Sheehy in 1896, and they married in 1903. They shared their socialist and nationalist views, and as ardent feminists, the Sheehy-Skeffingtons co-founded the Irish Women’s Franchise League in 1908. Francis was a committed pacifist, and had campaigned against recruitment to the British Army regiments in 1914 at the outbreak of the war in Europe. He had also opposed the increasing militarisation of nationalist organisations such as the Irish Citizen Army, and when the Rising broke out on 24 April 1916, he went to the city centre to appeal for calm. On the evening of Tuesday the 25th, on his way home to 11 Grosvenor Place, he was arrested and brought to Portobello Barracks. Although a search revealed nothing more than a draft form of membership of a proposed civic guard (to prevent looting in the city), and no charge was made against him, he was detained for further enquiries.

Francis Skeffington met Hanna Sheehy in 1896, and they married in 1903. They shared their socialist and nationalist views, and as ardent feminists, the Sheehy-Skeffingtons co-founded the Irish Women’s Franchise League in 1908. Francis was a committed pacifist, and had campaigned against recruitment to the British Army regiments in 1914 at the outbreak of the war in Europe. He had also opposed the increasing militarisation of nationalist organisations such as the Irish Citizen Army, and when the Rising broke out on 24 April 1916, he went to the city centre to appeal for calm. On the evening of Tuesday the 25th, on his way home to 11 Grosvenor Place, he was arrested and brought to Portobello Barracks. Although a search revealed nothing more than a draft form of membership of a proposed civic guard (to prevent looting in the city), and no charge was made against him, he was detained for further enquiries.

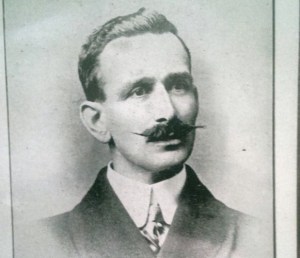

At this time, Portobello Barracks was officially under the command of Colonel McCammond who was absent on sick leave, leaving the command to Major James Rosborough. The barracks was also suddenly filled with soldiers from numerous regiments who were on leave in Dublin and reported for duty to their nearest barracks when the Rising broke out. The site must have been in a state of some confusion. Captain Bowen-Colthurst of the Royal Irish Rifles, originally from Dripsey, Co. Cork, was a decorated officer. He had fought in the Boer War and afterwards served in India, including the 1904 British military incursion into Tibet. He had been injured while leading a disastrous attack against a German position on the western front in September 1914 and was sent back to Ireland. He was attached to the 3rd Battalion stationed at Portobello Barracks when the Rising broke out.

It seems Colthurst became quite frenzied at the outbreak of the Rising. In the late hours of Tuesday 25 April he led about 40 soldiers out of the barracks in search of ‘Sinn Feiners’ (the Sinn Fein party were at that time mistakenly believed to be responsible for the Rising), taking Sheehy Skeffington with him as a hostage. As they headed towards the city Colthurst shot dead James Coade, a 19 year old mechanic, on the Rathmines Road. Richard O’Carroll, the Labour Party Councillor and Quartermaster of C Company, Irish Volunteers was delivering ammunition to the garrison outpost at Northumberland Road when he was pulled from his motorcycle and shot through the lungs. O’Carroll later died of his injuries on 5th May. Another man, Patrick Nolan was shot by Colthurst outside Delahunt’s Grocery shop, but brought to the hospital at Dublin Castle and survived.

It seems Colthurst became quite frenzied at the outbreak of the Rising. In the late hours of Tuesday 25 April he led about 40 soldiers out of the barracks in search of ‘Sinn Feiners’ (the Sinn Fein party were at that time mistakenly believed to be responsible for the Rising), taking Sheehy Skeffington with him as a hostage. As they headed towards the city Colthurst shot dead James Coade, a 19 year old mechanic, on the Rathmines Road. Richard O’Carroll, the Labour Party Councillor and Quartermaster of C Company, Irish Volunteers was delivering ammunition to the garrison outpost at Northumberland Road when he was pulled from his motorcycle and shot through the lungs. O’Carroll later died of his injuries on 5th May. Another man, Patrick Nolan was shot by Colthurst outside Delahunt’s Grocery shop, but brought to the hospital at Dublin Castle and survived.

When the raiding party reached Camden Street they entered the tobacconist shop of Alderman James Kelly, arrested Thomas Dickson (editor of The Eye Opener) and Patrick McIntyre (editor of The Searchlight), and brought them to Portobello Barracks. The soldiers fire-bombed the shop on Colthurst’s orders. Kelly was not present at the time and, though unconnected to the Rising, he was later arrested and interned, and released 16 days later.

At the barracks, Colthurst ordered that the three civilian prisoners be taken from the detention rooms in which they were held and brought to the yard. At about 10am on the morning of Wednesday 26th he ordered a firing squad of 7 soldiers to shoot the three civilian journalists. In a moment of clarity, Colthurst reported the action to his superior, a Major James Rosborough, saying that he had shot the three prisoners on his own responsibility and that he might possibly be hanged for it. Rosborough asked him for a written report, and Colthurst was confined to barracks duties. The bodies were hastily buried in the grounds.

At the barracks, Colthurst ordered that the three civilian prisoners be taken from the detention rooms in which they were held and brought to the yard. At about 10am on the morning of Wednesday 26th he ordered a firing squad of 7 soldiers to shoot the three civilian journalists. In a moment of clarity, Colthurst reported the action to his superior, a Major James Rosborough, saying that he had shot the three prisoners on his own responsibility and that he might possibly be hanged for it. Rosborough asked him for a written report, and Colthurst was confined to barracks duties. The bodies were hastily buried in the grounds.

On Friday 29th April Hanna Sheehy Skeffington arrived at the barracks to enquire about her husband, having been told by the police that she should ask there. Colthurst denied all knowledge of her husband, and threatened her with arrest. That evening, he led a party of soldiers in a raid on her home as she was putting her son, Owen, to bed, and took a large quantity of papers and books with the intention of finding incriminating evidence to justify the shooting. One paper that was probably found in this raid and produced at Colthurst’s eventual court-martial was a copy of the widely available Secret Orders Issued to the Military (the forged ‘Castle Document’) with the claim that he found it on Francis Sheehy-Skeffington’s person when he was arrested.

On Friday 29th April Hanna Sheehy Skeffington arrived at the barracks to enquire about her husband, having been told by the police that she should ask there. Colthurst denied all knowledge of her husband, and threatened her with arrest. That evening, he led a party of soldiers in a raid on her home as she was putting her son, Owen, to bed, and took a large quantity of papers and books with the intention of finding incriminating evidence to justify the shooting. One paper that was probably found in this raid and produced at Colthurst’s eventual court-martial was a copy of the widely available Secret Orders Issued to the Military (the forged ‘Castle Document’) with the claim that he found it on Francis Sheehy-Skeffington’s person when he was arrested.

Major Sir Francis Vane, serving out of Portobello Barracks, had reported Colthurst’s actions to the authorities in Ireland during the week but found them not only unreceptive to the complaint, but himself relieved of his duties, and the subject of a campaign against his character. He then reported to the military authorities in London, which led to Colthurst being placed under open arrest on 6th May. He was court martialled on 6 June and found guilty of the murders, but insane. He was admitted to Broadmoor Lunatic Asylum for one year, after which he was found to be recovered and released. He emigrated to Canada on a military pension where he died in 1965, never returning to Ireland. His family home in Dripsey was burned down during the War of Independence as retaliation for the murders.

Sir Francis Vane found that his actions in reporting Colthurst led to the ruin of his career, being relieved of his employment in the military, and all his attempts to publish his experiences were foiled by the military censor.

In December 1935 Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, who had campaigned tirelessly for justice for her husband, received a parcel containing a half brick with a .303 bullet embedded, accompanied by a letter explaining its context from F. McL. Scannell. It tells the story of how he came to have the object.

Dear Mrs Sheehy Skeffington,

The following is an account of how a half brick, in which is embedded a bullet that passed through your husband’s body, came into my possession.

I always considered that you should have it, but considered it too gruesome a souvenir to offer you.

After the three unfortunate victims had been murdered Bowen Colthurst made frantic efforts to wipe out all the traces of his crime which, in the shape of three sets of bullets in the wall, proclaimed to all and sundry who passed that way one of the first actions of ‘a Soldier and a Gentleman’ with which we became so familiar as the struggle went on.

With that object he had several bricklayers, who were working on a large building then being built for the British Government in Dublin, were taken with their tools, in basses, a kind of soft basket without cover but having two handles for carrying them by, to Portobello Barracks.

They were kept surrounded by British Soldiers with fixed bayonets, pointed at them. There were kept for a considerable time in this uncomfortable position, and then harangued at considerable length as to the consequence of divulging anything whatever of what they saw or did.

They were then marched with their ‘escort’ to the wall where the ‘executions’ had been perpetrated, still surrounded by fixed bayonets. They were then instructed to remove all the bricks with bullets in them and replace them with new ones which Colthurst had already a supply awaiting.

While this was being done the soldiers told them where each of the victims had stood. The spot being repaired by the man I knew was where your husband had been placed.

When the work had been completed the old bricks were left in a heap, obviously for the British to destroy.

The bricklayers were once again marched away and given another lecture as to what their fate would be if they breathed a word of what happened in the Barracks. They were kept surrounded by the wall of bayonets for a considerable time, evidently to ensure that their nerves were in the proper condition, before being marched to the gate where with a final caution they were sent away.

It was during this last tirade of frightfulness that the man I knew noticed that a portion of a brick was in his bass. He was too frightened to say anything about it. I met him shortly after and he told me what had happened and made me promise not to give him away. He asked me what he should do with the brick as he was afraid to keep it. I told him I would take it and he gave it to me.

I have kept it in my house ever since.

I tried through some of the ‘Boys’ to get in touch with you shortly after I got it but you were then endeavouring to reach America, and I could not do so.

Although I knew you were the one with the greatest right to it I could not bring myself to offer such a ghastly memento and so rake up wounds which will never be forgotten.

The findings of 1916 court martial remained controversial, and it has been asserted from that time that the military conducted a cover up in order to ensure that his commanding officers could not be held responsible for Colthurst’s actions. A conclusion of ‘Guilty, but insane’ allowed the event to be put down as the actions of an individual mad man.

But the existence of the bullet in the brick raises a question – if Colthurst was responsible for the order to replace the damaged bricks, does this imply that he was aware of what he had done and what the consequences would be, and deliberately attempted to cover the crime? Would such an action then prove compos mentis – that Colthurst was sane?

Evidence given in the court martial portrayed various sides of the officer. Some testified to his character, describing him as kindly and considerate, but more unbalanced after his return from France. Major General Bird’s testimony on made clear that Colthurst recklessly sacrificed his men during the actions around the retreat at Mons and at Aisne in 1914, remarking that when agitated and fatigued he was not responsible for his actions.

Dr Parsons had treated Colthurst on his return from the front and noted his extreme nervous exhaustion at that time. He saw him again at the time of the court martial and opined that he was close to a nervous breakdown, relating how Colthurst talked mostly about the fighting at Mons and how he spent time reading the Bible in the hours before the shooting of the journalists.

Captain E.P. Kelly testified that he witnessed Colthurst in Portobello Barracks on the day of the shootings; ‘half lying across the table with his head resting on his arm, and he looked up occasionally and stared about the room, and then fell forward again with his head on his arm’. Such evidence would suggest Colthurst was suffering from shell-shock, now known as post-traumatic disorder.

However, Colthurst was also known to occasionally commit acts of an ‘eccentric’ nature. A Major Goodman of the Curragh Camp had known Colthurst since 1904, when they were stationed in India. He told of how he shot a dog that had barked during the night. When he asked if the dog was dead Colthurst answered no, but that it was sufficiently wounded to die. This, alongside rumours of previous brutalities against prisoners and civilians, would indicate a tendency towards brutal behavior. Colthurst himself professed that he was carrying out his duty, believing he had the right to shoot rebels under the terms of martial law, and that in any other country except Ireland it would be recognized as right to kill rebels. Certainly, his raid on the Sheehy Skeffington household in an attempt to find incriminating documents would suggest that Colthurst was sane enough to determine what he needed to find to defend his actions.

There are conflicting memories surrounding the repairing of the wall in Portobello Barracks, with one claim that the military organized for the Royal Engineers to fill in the bullet holes, and another, Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, saying that bricklayers were brought in by Colonel McCammond on 7 May, the day after Colthurst was placed under arrest, to replace the bloodstained bricks with new ones. The account in the letter that accompanied the brick is the only one of the three that suggests Colthurst himself organized the repair, but contains no date or other details to support this and may have been a natural assumption at the time on the part of its author.

However there is little doubt that the brick did in fact come from a bricklayer who was forced to repair the wall, and is the material evidence of the attempt to cover the murder of the three journalists in Portobello Barracks in the middle of Easter Week 1916, whether by the military authorities or by Colthurst.

© Brenda Malone. This work is original to the author and requires citation when used to ensure readers can trace the source of the information and to avoid plagiarism.

https://libguides.ucd.ie/academicintegrity/referencingandcitation

Sources and general reading used in the creation of these articles are listed on the Further Reading page.

30 replies on “The Bullet in the Brick – the murder of Francis Sheehy-Skeffington and the madness of Captain Bowen-Colthurst, 1916”

What a brilliant story on such an unusual item.

I am delighted to have found your blog online – I am currently working on an artistic project for Cathal Brugha Barracks that responds to the decade of centenaries and in particular any events related to the then ‘Portebello Barracks’. I am particularly interested in the emotional and more human stories behind the historical narrative and the story of ‘the brick’ is a real gem. I would love to see it – if possible?

that letter to Hanna sheehy Skeffington is factual, I have the reply from her to my Grandfather Francis McL Scannell who was IRA Intelligence for General Michael Collins at the time, Lovely to see it published.

Hi Frank – that’s amazing! Would you be able to tell me any more about your grandfather? And Hanna’s reply? It’s great to know his full name for a start!

My Grandpa’s full name was Francis McLoughlan Scannell, I have Hannas Reply which I could scan,for all to read, but there is no facility here to do this.

I have several interesing items and Letters which have never been seen by anybody since that time

Would love to see them and learn a bit more – if you’d like to bring them in to Collins Barracks sometime you can contact me through the main museum number – 01 6777444, and ask for Brenda Malone!

It would be great to for everyone to see these items and letters from Frank and hope Brenda can post them here soon.

Yes I also am very interested to read these comments on this article as my great uncle Thomas Dickson was standing along side Francis Sheehy-Skeffington and Patrick Mcintyre on 26th April 1916 when they were murdered by Capt Bowen-Colthurst. In Sept this year we visited Dublin and went to Cathul Brugha Barracks Visitor Centre .

A local historian from the barracks now believes the men were killed at another wall behind the exercise yard of the guardroom. This wall is now marked as number 11 on the walking tour of the barracks. We now find this puzzling as this doesn’t seem to match other evidence from witnesses at the Court Martial and Royal Commission.Also after looking at the photos of the brick it’s size and shape are intriguing.

We are very interested to hear and see any information regarding this event Thanks Hugh

Thomas Dickson was my cousin, 3x removed, Hugh, I was just looking up your fathers info and found this. Samuel, father of Thomas killed in 1916, had a brother Thomas who,lived in Port Glasgow. I remember many years ago my Aunt Mary Dickson telling me about Thomas who was killed in Dublin and I’ve only just this past month made the connection.

There’s more detail about Bowen-Colthurst in the 2015 biography “A Terrible Duty: the Madness of Bowen-Colthurst” by Bryan Bacon. (I was the editor of the book).

Hi Jonathan we will look out for this book thanks

Hugh,

This is an Kindle ebook, available from the Amazon site (amazon.uk I think for Ireland)

Jonathan

Hugh,

I apologize for errors in the 6:06 am message. The message should have said:

This is a Kindle ebook, available from the Amazon site (amazon.co.uk I think for Ireland). Incidentally, you can read the first dozen or so pages on the amazon site to get an idea of the contents.

Jonathan

Hi Jonathan

Thanks again for the info on your book. We have purchased it through Amazon Australia, It looks to be a very interesting book and looking forward to reading it. Will be in touch with you when finished.

Cheers Hugh

HI Jonathan

Sorry for taking so long to get back to you in regards to your wonderful book you put together with Bryan Bacon ( A Terrable Duty).

We so enjoyed reading and getting so much information on Captain Bowen-Colthurst and the events of that terrible time in 1916.

I have made contact with the relatives of Richard O’Carroll who are putting together a week of commemorative events in April and have informed them

and other members of my own family about the book and have all expressed interest.

As we are also heading to Dublin in April for our own commemorative events we hope to be joining the O’Carroll family at a social/cultural event they have planned and members of the Sheehy-Skeffington family are also expected to attend. The aim is to gather as many family members together as possible that have fallen foul of Bowen- Colthurst.

Although no contact has yet been found of the families of Patrick McIntyre or James Coades. Are you aware of any contacts for them?

We are searching for a photo of Thomas Dickson, are you able to assist there also?

Sorry for being a bit long winded on this blog, but I could not find any other way to contact you.

Regards

Hugh

Hugh,

I am so pleased you enjoyed the book and hope that it will fill in some of the historical gaps .

On 9 February, 70 people attended a presentation at Penticton Museum and Archives on the life of the former local

resident – Captain Bowen-Colthurst. Some of the people knew him and were apparently quite shocked at what they found out at the presentation. They had no idea of his past. It must have also surprised any members of the local “British Israel Association” who might still be extant. (Colthurst was the vice-president)

One attendee related that Colthurst was an appalling driver and that at his last driving test, he adamantly refused to parallel park for the examiner. But he got his licence anyway. Plus ca change…

Colthurst’s house in Naramata is now the site of the Howling Bluff Estate Winery, which has as it’s logo a canine howling (with a bottle in its paw). But I would guess it’s not a drawing of the poor dog shot in India but merely a happy, local coyote.

I’m sorry I cannot help you with contacts for Patrick McIntyre, James Coade, or the lad who was shot (but who recovered?) around the same time that Councillor O’Carroll was shot. I hope you are able to connect with them.

I would very much like to know something of Thomas Dickson’s life – the memory of Colthurst’s last cruel words to him stays with me.

Jonathan

Hi Jonathan,

Thanks again for your contact. The book indeed filled in many historical gaps regarding Colhurst and my great Uncle Thomas.

I do not have alot of information about Thomas but if you would like to contact me at hughie3@yahoo.com.au I will send a few things onto you

Hugh

Well researched and educational article. Very well done 🙂

While researching on tthe history of Wales and the First World War at the Imperial War Museum three years ago I came across an interesting 9pp letter by a Welshman with the name W Jones [typically Welsh] who ran a window cleaning business in Dublin. He descibes events during the Easter rising including references to Skeffington. I am afraid I don’t remember much of the detail and, as it was not directly relevant to my research, I did not copy it. However you may be interested in it: IWM doc. no. 11086. I’m sure it would be worth pursuing. [We could do with a few Skeffingtons, Connollys et al in Wales these days.]

Hi Gwyn

Thanks for the info. Have made request to IWM for doc.

Cheers Hugh

Are there any available documents on the court-martial? I have a great-uncle who was with the 3rd battalion of the Royal Irish Rifles between late 1915 and mid 1916 and I’d be very interested to know what his involvement might have been. Perhaps the Kew archives would have some information?

My understanding is that the trial record was “withdrawn from the public domain”. However, Sean Enright’s new book “After the Rising” will cover the court martial and may indeed use recently released transcipts. James Taylor’s forthcoming (June) title “Guilty but Insane” will also be of great interest.

In the meantime, Bryan Bacon’s ebook “A Terrible Duty” discusses the trial . His account is based on The Irish Times, The Irish Independent, and The Times for June 7/8, 1916. I think the Kew documents are: PRO 35/67/1 and PRO WO 374/14934. There’s about a foot of documents there.

Good luck with the search on your great uncle. I’d be interested in your findings.

Jonathan O’Grady

Thank you very much Jonathan. I’m planning a trip to London this Summer, so I’ll certainly try to get through some of those documents. I’m wary of what I might find, but curiosity has got the better of me!

Thanks Jonathan – the document reference numbers you gave me were very useful for my visit. Just for future reference, WO 374/14934 contained a lot of personal correspondence from Captain Bowen-Colthurst, who still seemed somewhat irrational and excitable long after his court-martial, repeatedly referring to his accuser Major-General Bird as ‘Judas’.

The larger file, WO 35/67/1 (sealed for 29 years after the events), contained a lot of documentation concerning the North King Street Massacre and the execution of the rebel leaders. The files relating to Bowen-Colthurst cover the preparations and aftermath of his court-martial at Richmond Barracks. This inquiry only sought the testimony of seven officers, including Major Rosborough, Lt. Morgan, Lt. Dobbin and Sgt. Maxwell of the 3rd Battalion Royal Irish Rifles, Sgt. John Aldridge and Lt. Wilson of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers and Lt. Morris of the East Surrey Regiment (who had originally arrested Francis Sheehy-Skeffington and taken him to Portobello Barracks). Sgt. Aldridge was commanding the guard at Portobello Barracks on the morning when Captain Bowen-Colthurst ordered the three civilian prisoners into the yard and seven members of Aldridge’s guard to form a firing squad.

The names of the rank-and-file soldiers involved are not listed here although solicitor Henry Lemass, acting on behalf of Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, had requested the names of the firing squad, the arresting officers, the search party, etc. However, the guard duty rosters from these few days are included, listing the soldiers on guard duty and the prisoners they held (generally drunk/AWOL soldiers, but joined on this occasion by the three civilian prisoners). I’m assuming the firing squad were drawn from the guards on duty that day, which didn’t include my great-uncle but did include other members of the 3rd Battalion RIR (among other regiments). It’s noted that there were about 150 armed soldiers at Portobello Barracks, more soldiers unarmed, and many civilians seeking refuge from the rebel-held surrounding streets.

Some interesting correspondence from this file relates that Dickson and McIntyre were arrested for associating with Alderman James Kelly, a constitutional nationalist whom the soldiers had confused with Alderman Tom Kelly of Sinn Fein. Attempting to justify the execution, an Alexander Blackadder reported seeing Padraig Pearse and ‘a 50-year-old German’ frequenting Sheehy-Skeffington’s house, while an ‘eccentric’ artist named McConnell claimed that he saw Sheehy-Skeffington in command of a rebel group which broke through his home on O’Connell Street.

All in all, while I didn’t locate any reference to my great-uncle, this was a fascinating bundle of papers.

Thank you Neil for this interesting information, especially who the prisoners were and the reason for Dickson’s and McIntyre’s arrest. Did you by any chance come across a transcript of the court martial?

Jonathan

No, I didn’t see any transcript, just the invitations to the seven officers to attend and various other legal notices concerning the court martial.

[…] Captain John Bowen-Colthurst (The Cricket Bat that Died for Ireland: Objects from the Historical Collections of the National Museum of Ireland) (this particular post is a fascinating account of Bowen-Colthurst’s bloodlust and its aftermath) […]

‘Guilty but Insane: J.C. Bowen-Colthurst: Villain or Victim’ will be released by Mercier Press on 3 June 2016 and corrects many published errors about the entire episode. It includes his court martial, together with extracts from his Military, Home Office and Pension files. I had the assistance of members of the Sheehy Skeffington family and a daughter of Bowen-Colthurst who gave me access to his personal papers. There is a photo of Thomas Dickson in Kilmainham Gaol Archives.

Hello, I’ve just read this interesting post. Until recently, the only personal connection to the events in Ireland that I knew of was an English grandfather on one side, who was in the Worcestershires in Dublin in the 1920s … but I learned this year that Patrick and Willie Pearse were second cousins of my English great-grandfather’s brother’s wife on the other side. 😉

I’m wondering whether the contributors here have seen the newly digitised records available at FindMyPast. I did a search for ‘Colhurst’ and the results are here:

http://search.findmypast.co.uk/results/world-records/easter-rising-and-ireland-under-martial-law-1916-1921?lastname=colthurst

— from what I can tell, all referring to the individual pages within the set of 422 images: HO 144/21349

(Not yet digitised at the National Archives: http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C4167137)

They don’t seem to be in chronological or reverse chronological order. The first page is from 1935, the last page is from 1918, page 100 is from 1916 …

At page 103 is the report of the Royal Commission. A lot of the rest seems to relate to Bowen-Colhurst’s irrational conduct in later years.

This may be old news, but anyone interested might want to take a one-month subscription at FMP in order to access and download the images in the file.

Bowen-Colhurst’s treatment contrasts interestingly with that afforded my above-mentioned grandfather, who was discharged from the Dragoon Guards several years before WWI at the age of 16 (having enrolled at 15 stating a false age) ‘with ignominy’ — a fate reserved for non-officers — for possession of stolen goods. (Like many men with similar fates, he re-enrolled under a false name, ultimately receiving a battlefield commission; the records at FMP show him leading raiding parties in Ireland in 1921.)

The family of Bowen Colthurst resided in Berechurch Hall road, Colchester. The IRA planned to bomb the family house in the 1930’s but the plan was never executed. My grandmother, originally from Co. Tipperary was asked to help, but declined.